Comic book Scripts are Weird (w/ Examples!)

How to write a comics script

Hey Comics People,

Have you written a comic book script? Got one in mind? Or maybe you’re just curious to see what they look like?

This post is for you.

Personally, I wish I’d looked at more comic scripts before I finally got around to writing my own. Heck, I wish I had reviewed more examples before yesterday. But we’re here now, and that ain’t nothing. So check out the examples included below and let’s consider how to write better scripts in today’s issue of…

Scroll on down and you’ll see that I’ve compiled a bunch of examples of comics scripts. Take a look at ‘em and consider their respective formatting and manner of communication. Rather than offer too many of my own insights, I’ll invite you to reach your own conclusions as to which examples might work best for your needs. I’m no authority on this subject. But keep in mind that, for your own scripts, you can mix and match, as most tend to do. Use any and all lessons as you see fit to communicate effectively.

Oh, and in addition to the examples below, I tracked down a killer example of two scripts by comics writer Matt Fraction. DEFINITELY hit that link and take a look at these two scripts. Fraction shares examples from two of his scripts, one for artist Howard Chaykin, and another for artist David Aja…

Fraction states that Chaykin wants: “what’s called a FULL SCRIPT. He wants me to guide him and offer visual notes and to see where my cutter’s instinct finds edits and beats. Then he either executes or improves upon those ideas.” Whereas for Aja, Fraction produces more of a ‘Marvel Method’ script, which means he just shares the general plot beats to be hit on a page, trusting the artist to block the action and movement, after which time the writer will take a look at the page composition, character expressions, etc and use the completed visuals to dictate the final dialogue / scripting to best accompany the artist’s work.

The Marvel Method is a proven strategy, but cutting back to Fraction’s example when working with David Aja: quite notable in that specific scenario is the fact that David Aja is an artist with whom Fraction had worked with on hundreds of comics pages already. More specifically, of Aja’s script Fraction says: “If it’s David, and it’s HAWKGUY, it looks like this [link to see the reference he shares], EDIT because it’s PLOT STYLE and i learned on IRON FIST [a previous series these two worked on together] to SHUT UP and GET OUT OF DAVID’S WAY.”

These two examples, taken together, serve as one hell of an illustrative example. Especially because they both come from the same writer. Let’s assume that each artist produced a maximal end result off the scripting style delivered to them (and in my opinion, the end results of each effort suggests it worked well!). Fraction’s example then suggests that different artists require or expect wildly different levels of communication from their writing partners.

Okay, we’re gonna dive into more examples soon, and look at how they’re structured. But we’re circling a vital point that I want to be sure is hammered one a bit first. So lets hang ten for a beat and maneuver our way into what might be bringing us to question a comic script’s formatting and sliding scale level of detail…

My experience in identifying resources for writing comic scripts was disappointing…

When I was looking for a good resource for writing comic scripts, I discovered that it didn’t exist. Along the way, the resource that disappointed me the most was Words for Pictures: The Art and Business of Writing Comics and Graphic Novels by Brian Michael Bendis…

This book didn’t compell me to dive immediately into writing a script like I had hoped it would. Quite the opposite, in fact. It left me kinda paralyzed… That said, despite feeling a bit deflated after my first read through Words for Pictures, I’m glad I picked it up. If I’m honest, Bendis is not my favorite comic writer. His scripts can be well more decompressed than I prefer from my comics storytelling. But he shared some immensely helpful information in this book. Information that, while it didn’t compell me to jump directly into writing a mile-a-minute, it did provoke some serious thought and consideration ahead of writing my next script.

So why, exactly, was I deflated when I read through it?

See, I went into that book looking for a step-by-step guide for writing comics scripts. Instead, my biggest take away was a key truth to scripting comics, a truth that made staring down the path feel MORE daunting, not less. It was stated bluntly by Mr. Bendis in the third chapter, appropriately titled ‘Writing for Artists’, and it was accompanied by examples that proved that the following statement was accurate. His statement and the accompanying proof sounds straight forward. But it leads into some serious challenges. The statement being that: “the function of your script is to communicate clear story, images, and characters to… the artist” and that “depending on your circumstances, the total audience for your script could be a whopping one person. Just one person.”

So a script needs to convey all that is necessary for a story tellers who are actually putting those lines on the page. Got it. Makes sense! So what’s the specific way we accomplish this? Surely we’re going to get that step-by-step guide next, right Mr. Bendis?

Wrong…

Inside the book Bendis gathers script examples from various comic writers, and guess what? They’re all wildly unique! Even at a quick glance it’s obvious that they’re formatted quite differently from one another. But drill down into each example provided and this to lack of uniformity goes far deeper than just the formatting. Some writers go into vivid detail, laying out specific panels and scene compositions. Others lay out some visual ideas but trust an artist to determine the page layout and number of panels. Most meet somewhere in the middle.

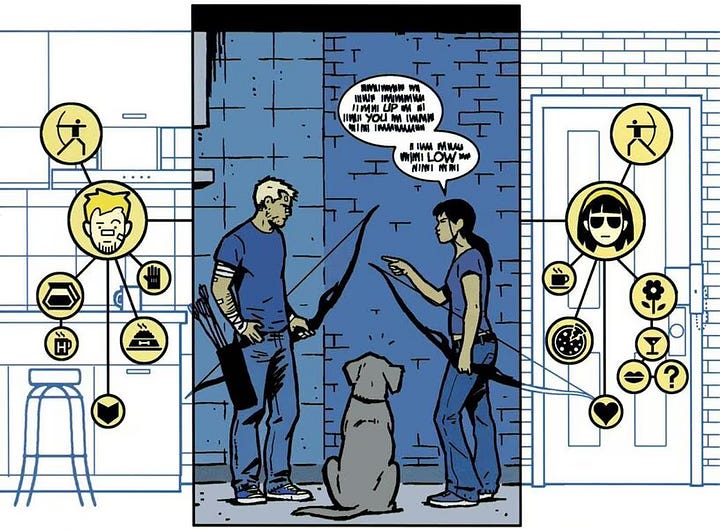

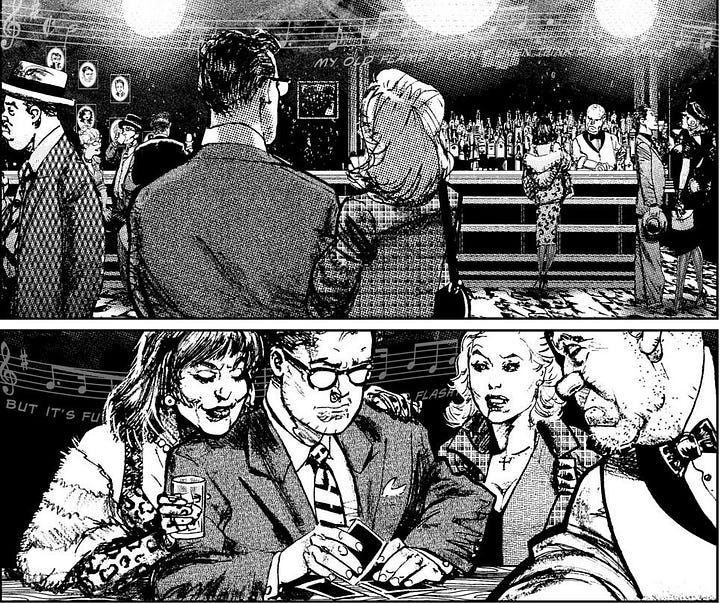

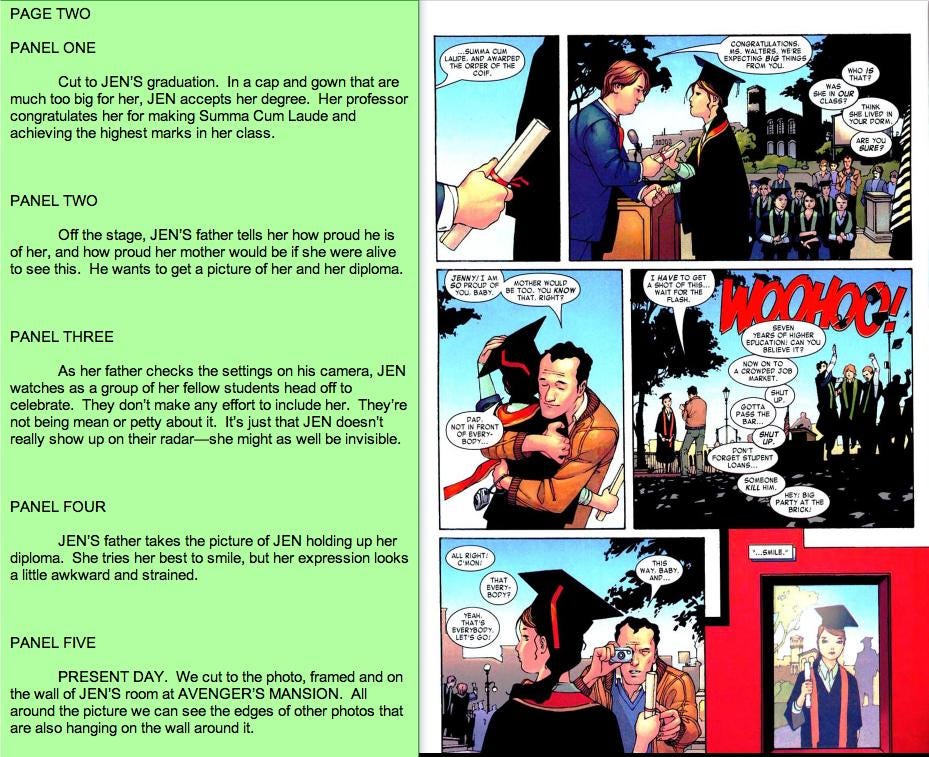

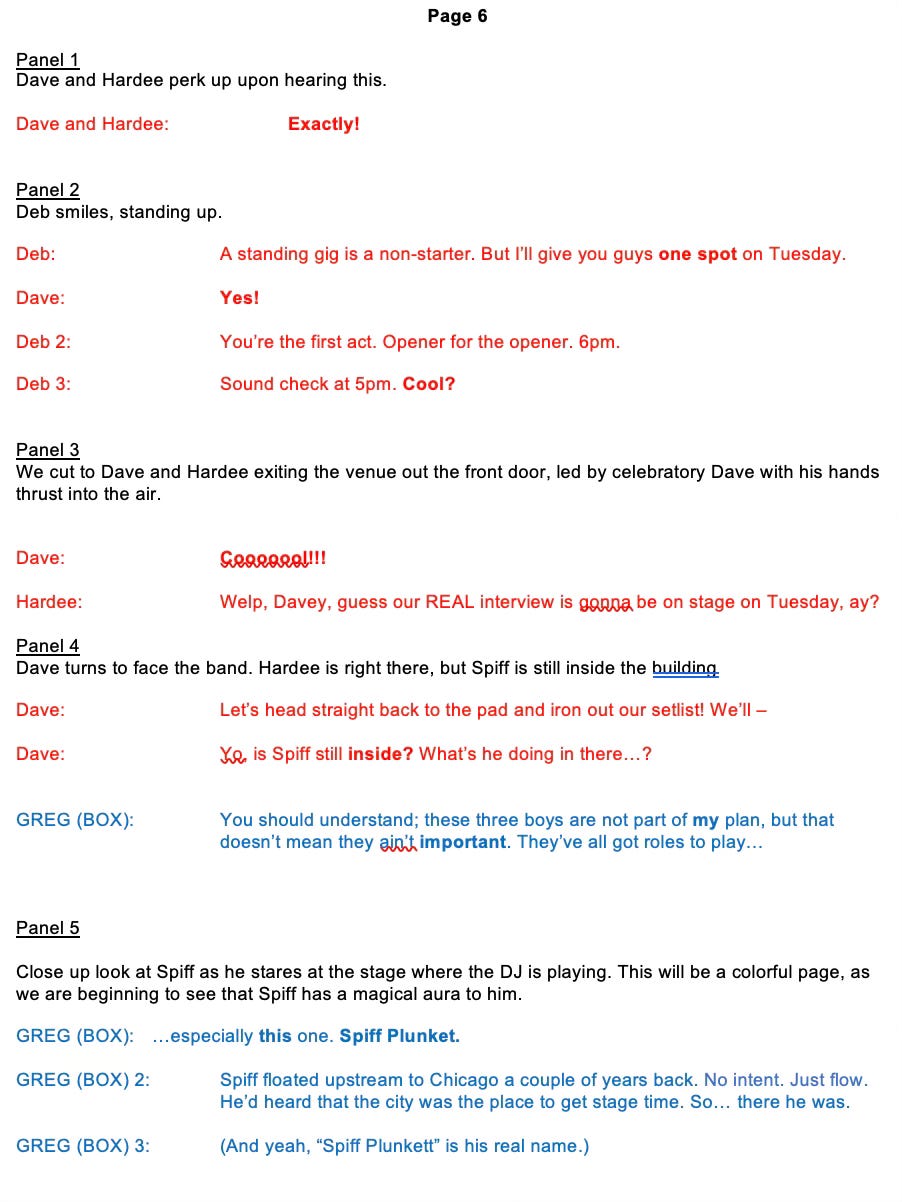

Here’s an example of a Marvel Method script and the resulting final page, shared by Brian Michael Bendis. It’s a style most often used by writers who work on a number of different books in a given month:

This is just the tip of the iceberg… Some writers adhere to screenplay standards that might look familiar to screenwriters or those who have spent time with stage scripts. Others? Wild freeform text. Chaos!

Even when formatting IS consistent between two different writers, the means of communicating visual ideas vary wildly.

Bendis hits the reader with this reality, hits ‘em hard with these examples. Points well made. But for me, this wild variation was disheartening. My plan to follow a step-by-step manual was shattered. And though I’m sure there are guides and individual writers who would offer a concrete format, selling at as the gospel, it’s all too clear that they’re no such thing. Goo practices? Yes. Specific standards for individual publishing houses? Yep. But facing the reality laid out in Words for Pictures is hugely helpful to process.

The crucial piece of intel is that comic scripts are a tool for communicating with artists. If an artist taking on a new comic project has spent time and produced great results with a specific format, then that form of script might be the winning strategy for that comics project. Otherwise, it’s on the creators to find their ideal means of communicating.

So?

So you need to know and understand your collaborators.

When it’s game time and you’re handing a script to an artist, for best results a writer needs to have as clear an understanding as possible for how this specific individual will best process information. You need to actually talk with you collaborators. Get to know their mind and how they process words into pictures. Assume as little as possible. What’s true of one collaborator might well be untrue for another.

The key distinction between a comic script vs a script for film or stage is that they’re not meant to communicate a full story or the movement of humans. It’s ONLY meant to communicate with the mind that’ll be moving those lines across the paper.

It’s on you to find out if that singular artist responds to a specific form of communication. Talk to them as much as you can and pay attention. If necessary, adjust your script to be as best attuned to THEIR needs as possible.

Okay, on to the actual examples!

Take a look at these scripts and the accompanying completed pages. Note the visual direction offered by each writer:

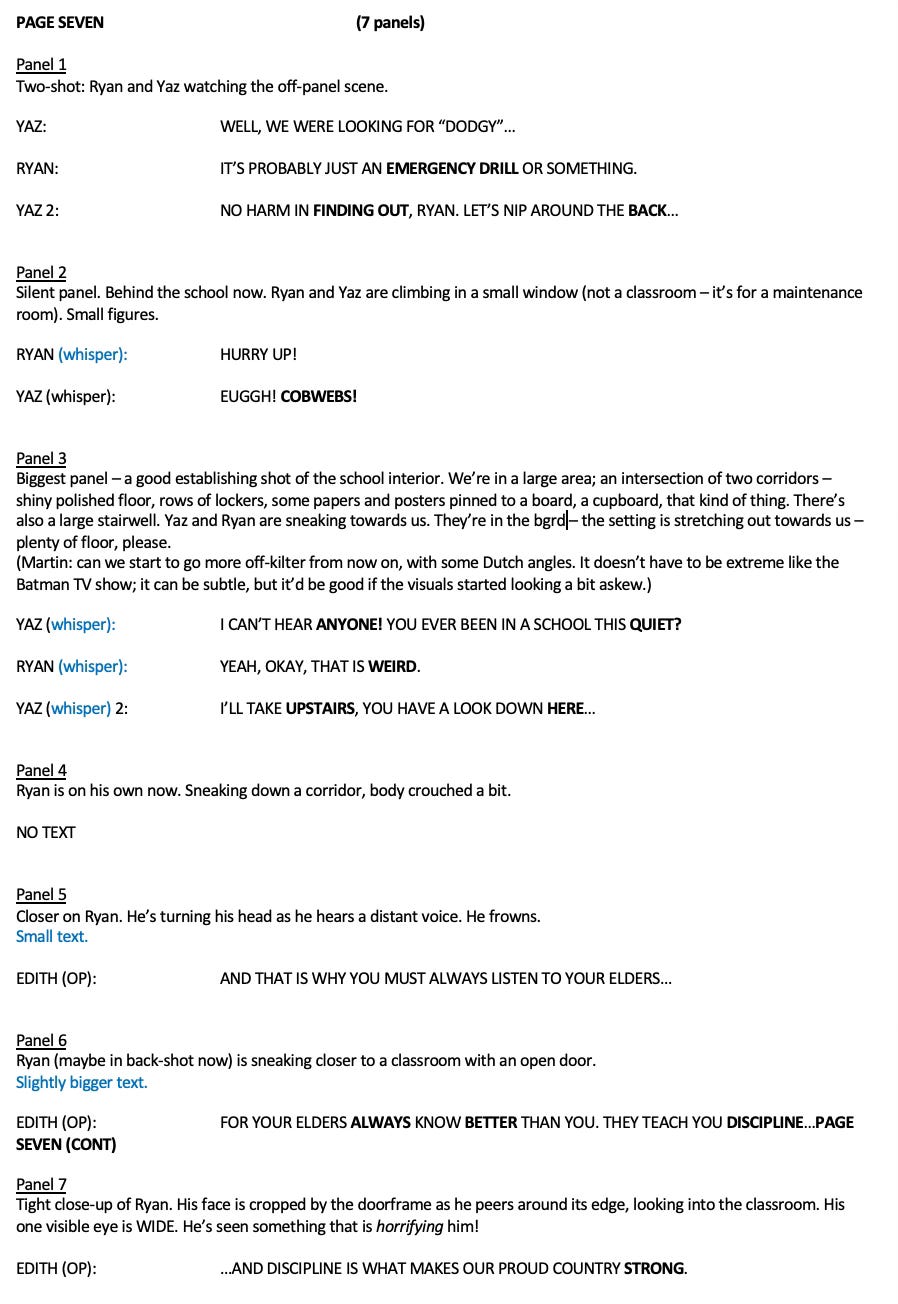

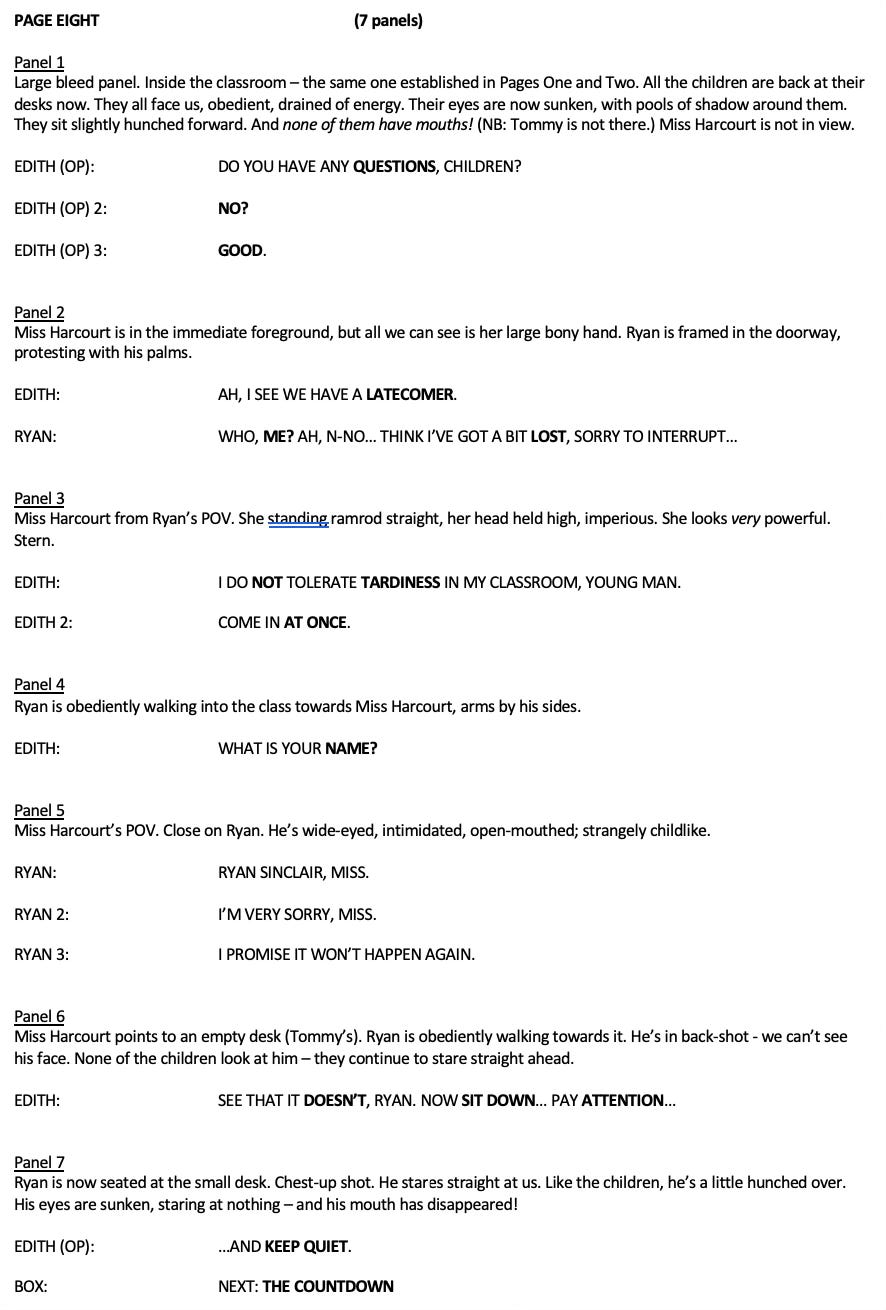

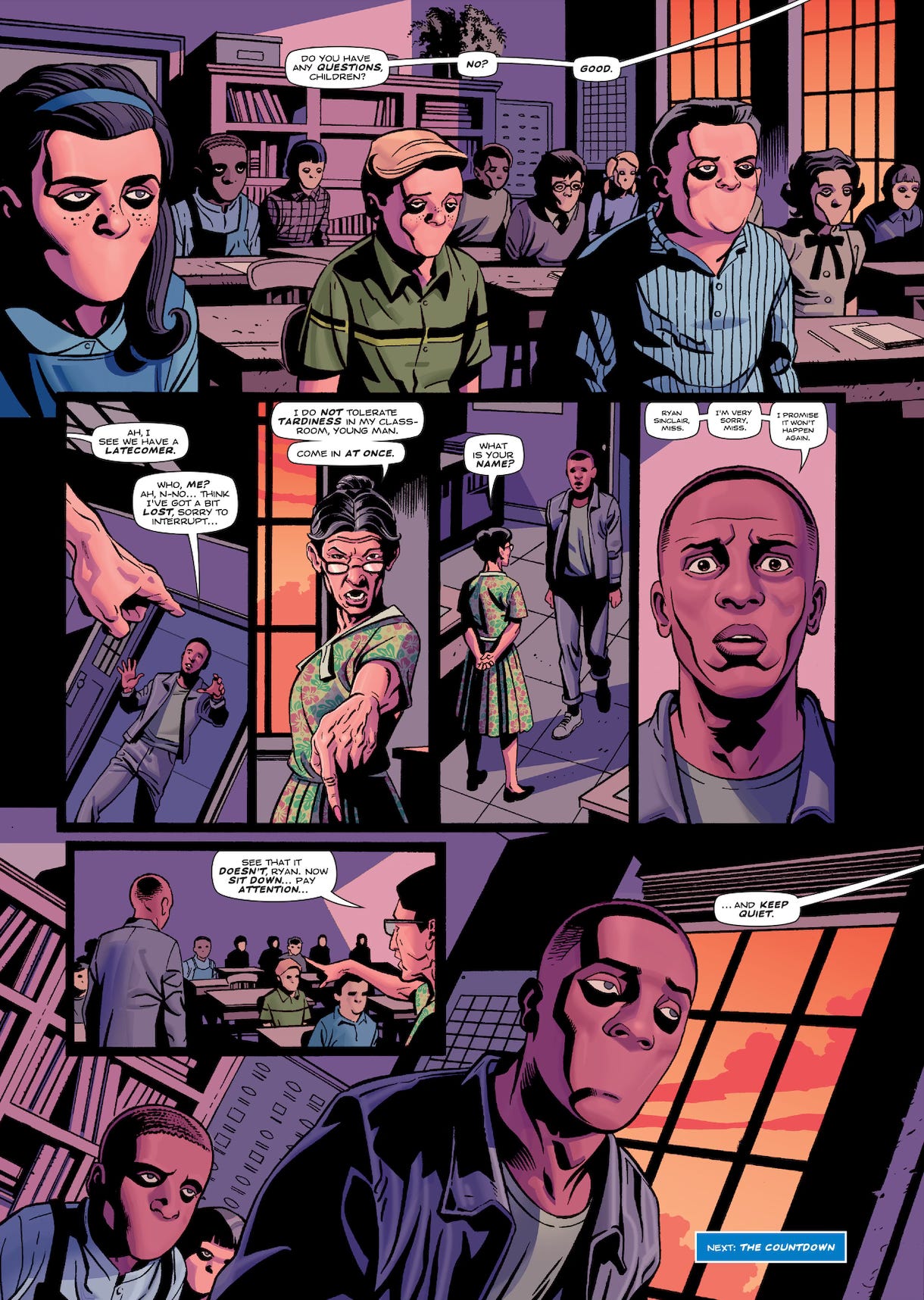

Here’s a great example from an awesome Doctor Who short story featured in Doctor Who Magazine in 2020. The story is titled ‘The Piggybackers’, from writer Scott Gray, with artist Martin Geraghty. It’s worth checking out the complete story if possible. In this script example, you’ll note that Gray communicates exceptionally well with his artist partners, painting a vivid picture in his own right:

Scott’s formatting is an excellent example to emulate. This is a script that will give an artist everything they will need, and is formatted to standards that will be immensely helpful for a letterer down the line as well. This is an across-the-board fantastic example.

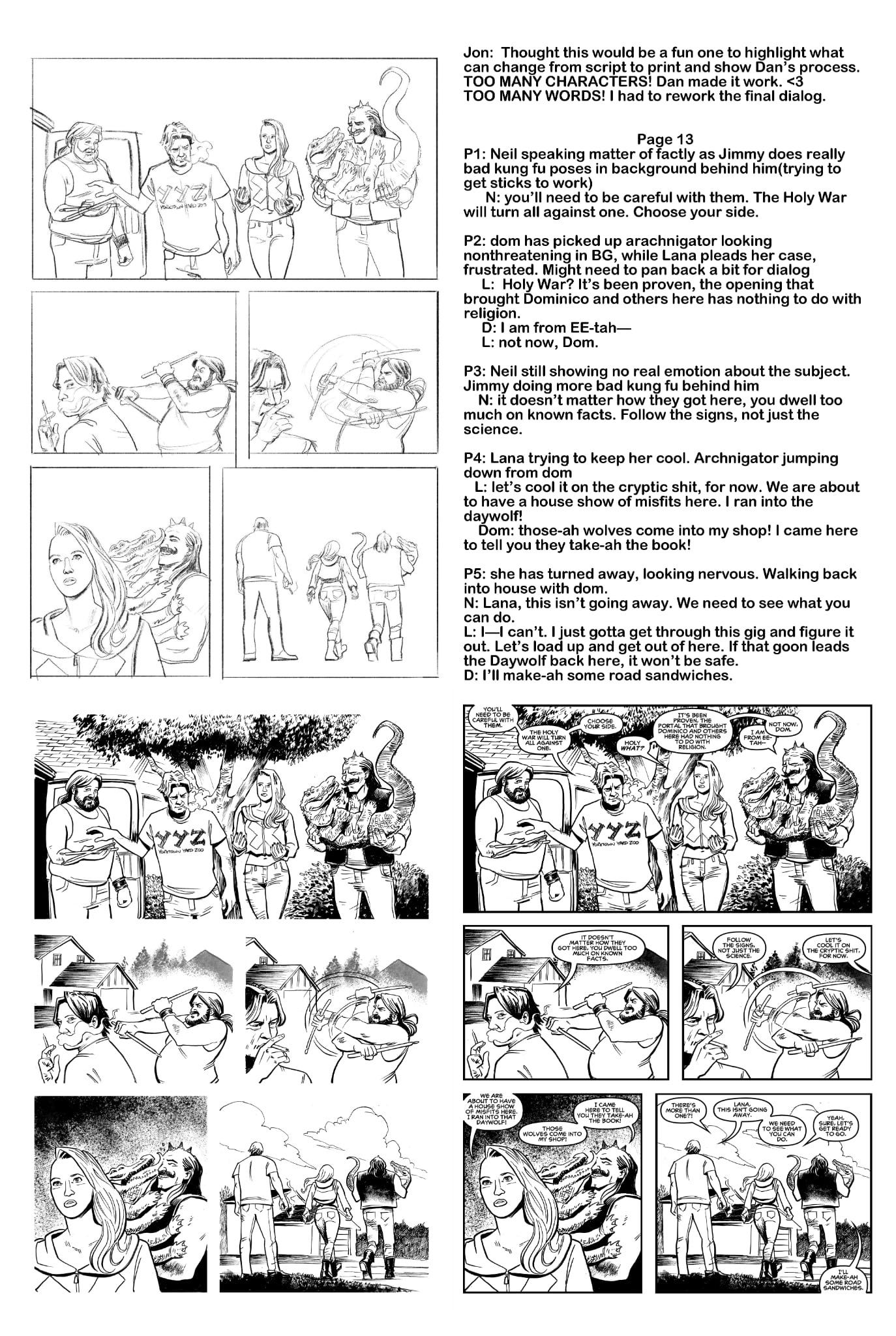

Taking another approach is writer Jon Westhoff communicating with artist Dan Daugherty. They communicate and work together extremely well. This was for an issue of Drumsticks of Doom (check out last week’s post for some awesome info about that book!). Check out this process sequence:

Worthy of note here is that, as was the case with Matt Fraction and David Aja earlier in this post, Jon and Dan have known each other for a decade or more and they have been working on this book together for years. Jon puts tremendous trust in Dan’s intimate understanding of these characters so he does not overburden with detail in this scene. Jon even makes some changes to the finished script, lettering his own work and making sharp decisions on the fly, a bit ‘marvel method’ style, as he takes a look at Dan’s completed page.

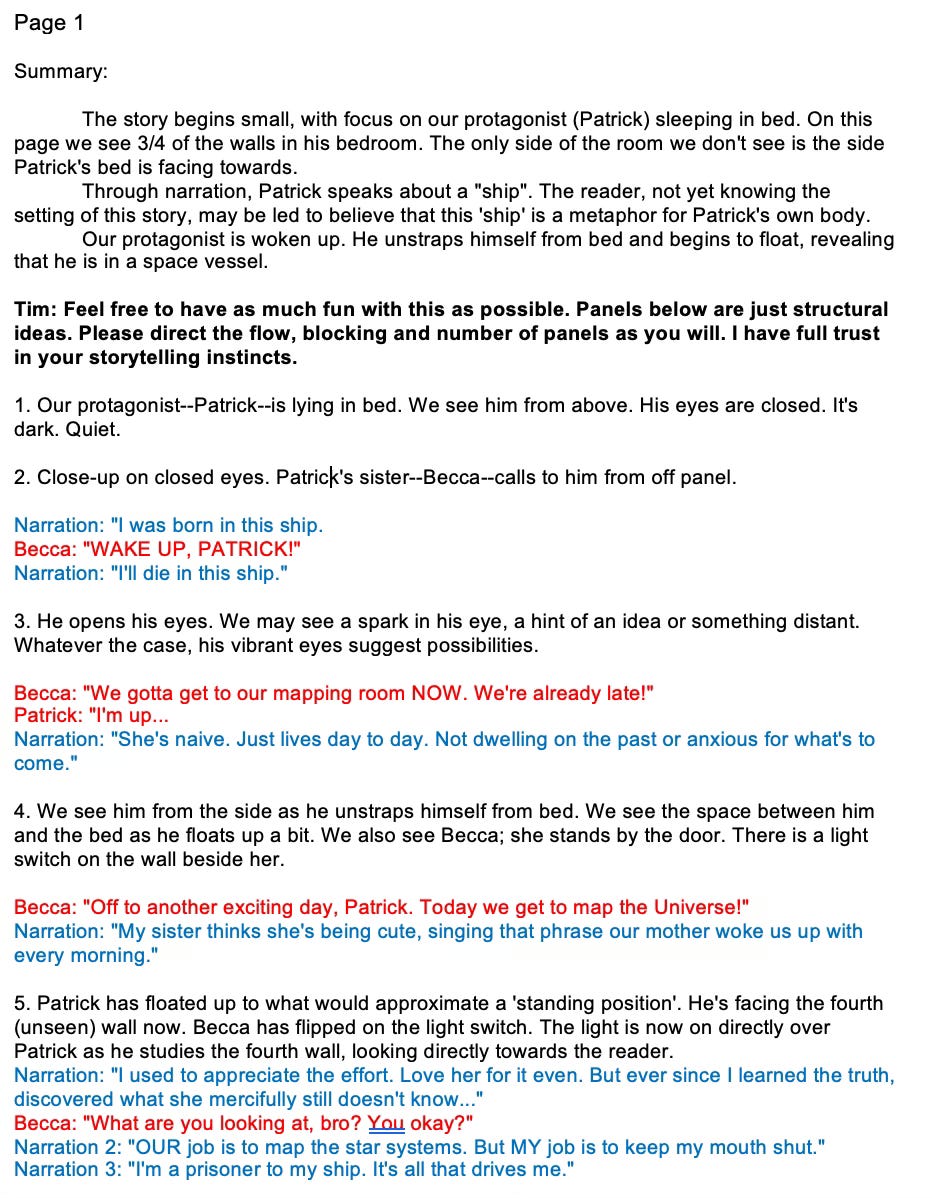

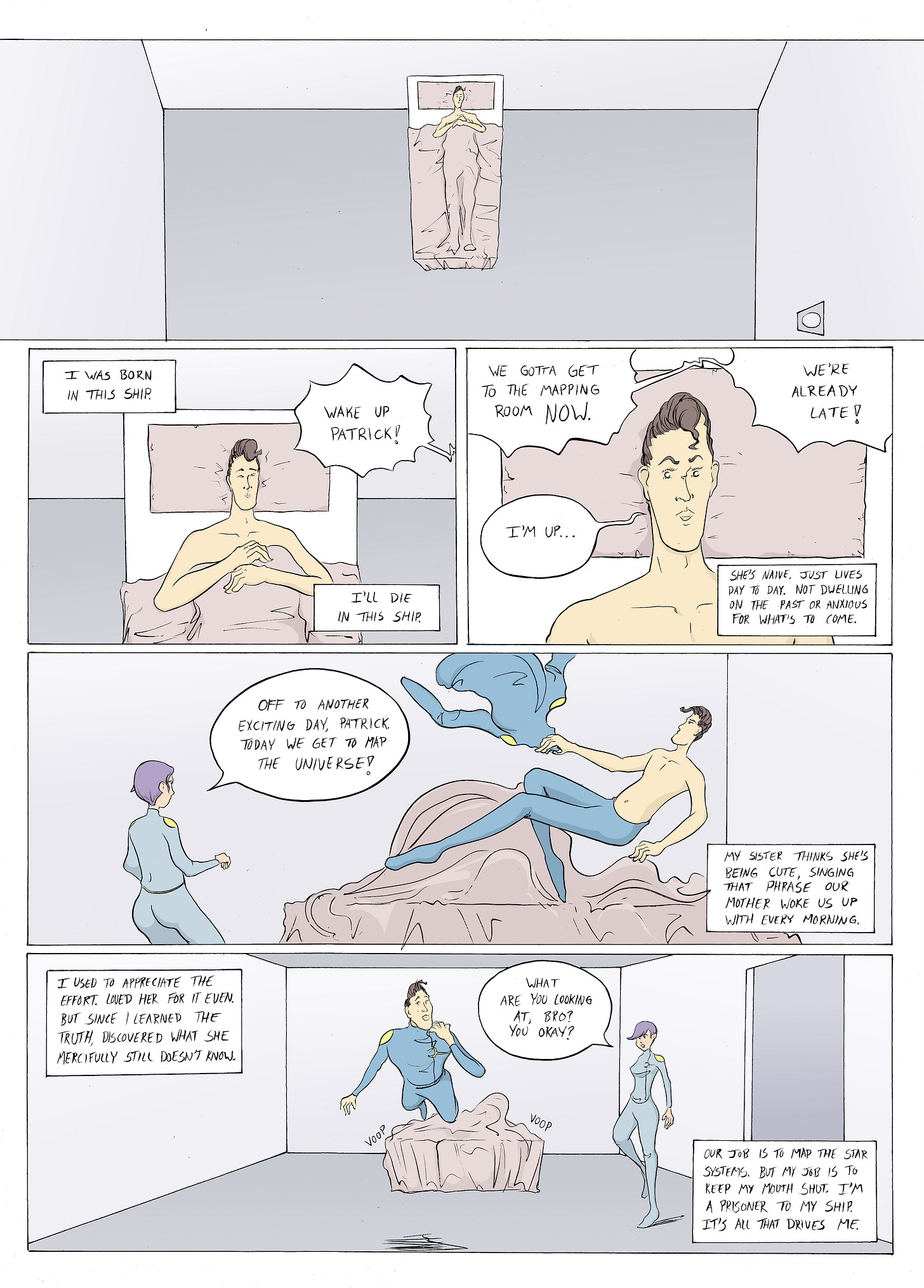

And here are two examples of different scripts I’ve written. Communicating quite different for each respective artist:

Here’s an early example of one of my first-ever comics scripts. This was for The Great Reach, with artist Timothy O’Briant. I never had the chance to actually TALK with Timothy, so the script is pretty full, and my formatting was very much a work-in-progress: If you’re curious to read more, I shared this full 8 page comic in the very first issue of the Making Comics blog (the blog which you’re reading RIGHT NOW, if that wasn’t clear!).

And here’s a more recent script page, from Big Shoulders #1, by myself with art by series co-creator Scott Gray. In this example, Scott and I had ample opportunity to discuss each individual page in detail, we’d even shared dozens of photographs for reference, allowing for a relatively sparse level of description for each panel:

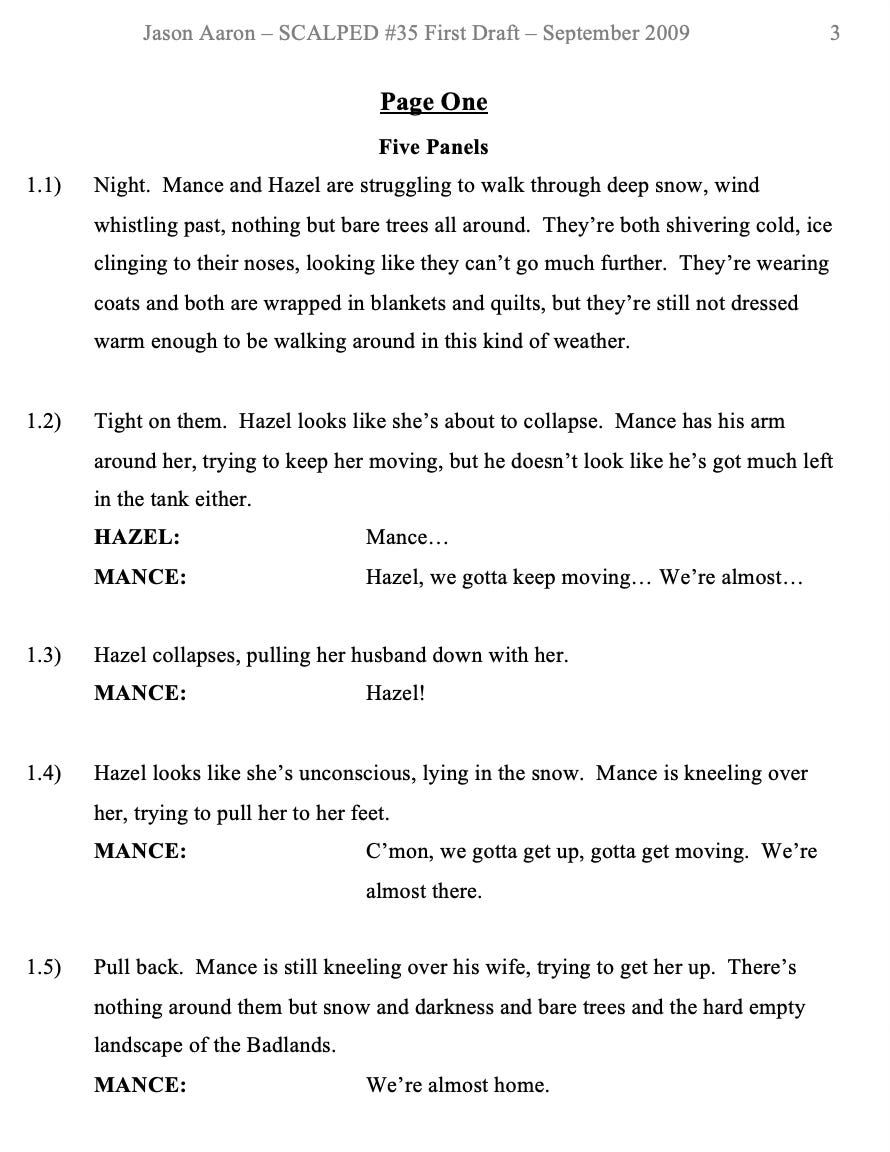

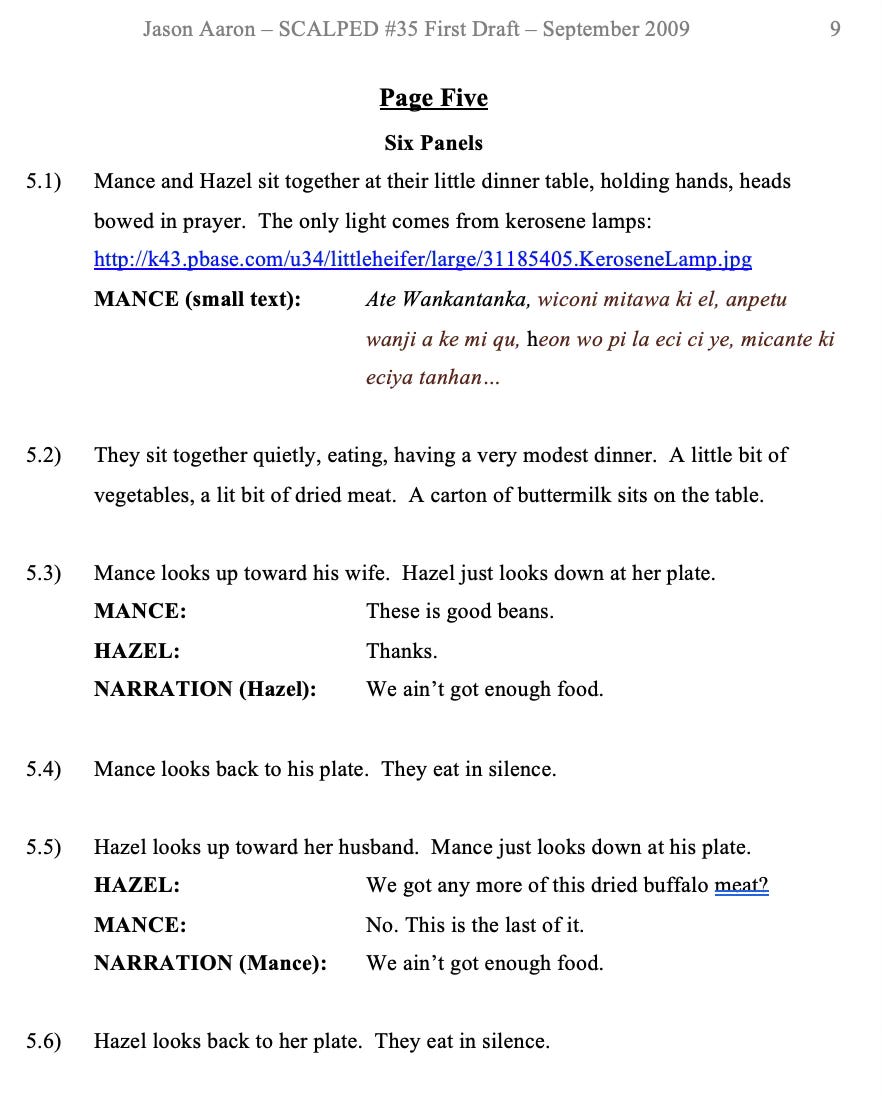

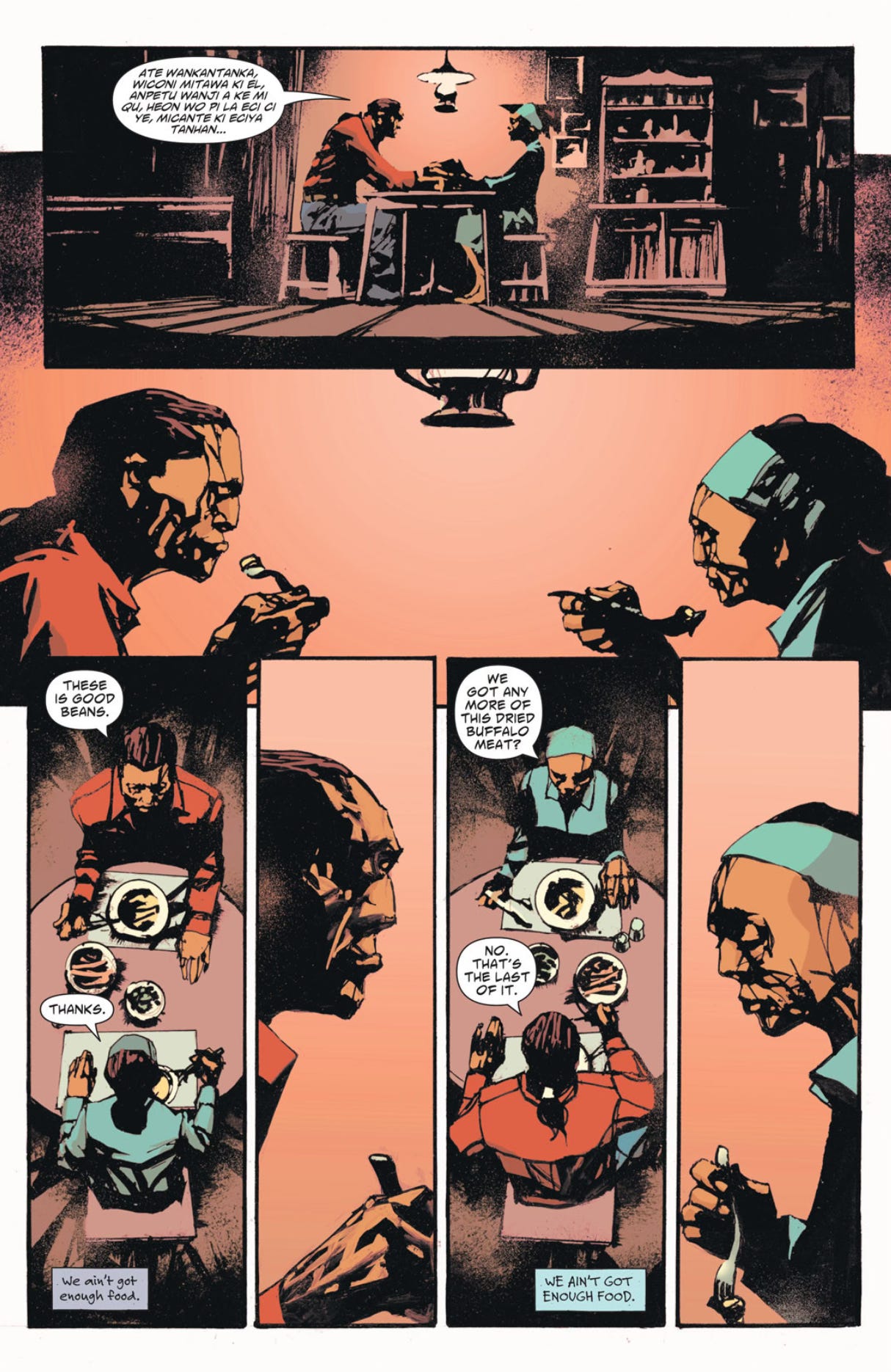

And finally, I want to leave you with an example that is not my own. Here’s an example from Jason Aaron, from a script for Scalped #35 which Mr. Aaron shared here, illustrated by Danijel Zezelj:

I told you I’d be sharing a lot of examples!

What has stood out to you most? Any examples look like a particularly useful format for you?

Fitting questions to ponder as we close out this week’s issue of…

John, the DC writing comics book by Denny O’Neil is the closest I have found to a step by step guide to writing comics. I agree with you, the Bendis book is daunting and I had to dig hard for any gold.

Fantastic post. I wrote a comic script, and in my early research, could not find a standard way that it was done. I found a link to a place that shared works from notable writers, and they were all so wildly different. Ever seen an Alan Moore script? The one I saw was written in all caps, and sounded more like a series of notes written for one specific person. Like a one way conversation. Anyways, thank you for the resources and excellent write-up. I’ll be reading this again several more times.